Author Interview

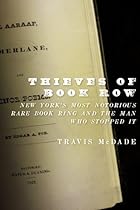

Travis McDade is curator of rare books at the University of Illinois College of Law, where he teaches a class called "Rare Books, Crime & Punishment." His second book Thieves of Book Row, was published in June by Oxford University Press.

Travis McDade is curator of rare books at the University of Illinois College of Law, where he teaches a class called "Rare Books, Crime & Punishment." His second book Thieves of Book Row, was published in June by Oxford University Press.

Set the scene for us, if you would, by providing a brief description of what Book Row was like during its heyday. Is there anyplace even comparable today?

Book Row was six blocks of Manhattan's Fourth Avenue packed with bookstores and personalities. Most of these shops were run by men who had learned the trade at the elbow of other booksellers, so there was a well-earned knowledge of the book business, of lower Manhattan and of other booksellers' aptitudes. These guys were well-read and hard-nosed. There is a tendency now to look back with the sort of nostalgic, moonlight-and-magnolia gloss we often do with the recent past—and some of that is deserved—but Book Row wasn't Disneyland. It was a labor of love for many of these guys, but it was definitely a labor. And life in Manhattan in the early 20th century was no picnic.

There are places now that have clusters of bookshops—Hay-on-Wye in the west of England springs to mind—but nothing like Book Row. What made it unique was a combination of these personalities, certain historical economic forces, and the nature of New York City at the time. It couldn't have existed anywhere else, and it can't exist now.

The theft ring you write about in Thieves of Book Row was no fly-by-night operation: these guys were organized! Give us a sense of how the operation worked, who was involved, and the impact these thefts had on the book and library world of the time.

Like most cottage industries, it developed organically. It started out as just some guys stealing books and selling them to shops—the classic American story!—and it grew from there. A confluence of events made this theft ring, like Book Row itself, possible. By the second half of the 1920s, there was reliable transportation, a decent economy and a rise in the value of a certain type of books. These books, as it happened, were sitting on the open stacks of libraries all over the American northeast, most librarians not even imagining they were worth the effort to steal. Once, at least, they had been right about that. But by the 1920s, it made good business sense to send men from Manhattan to Worcester, Massachusetts, to steal half a dozen books, if the men could then easily move on and hit Lancaster, Leominster, Gardner, etc. The thieves would get paid a standard rate of $2 per book and the bookstores would sell them for anything from $25 to $1,000.

Just to give an indication of how large the theft ring was, by the time it came to an end, the major problem was not getting the books out of libraries but finding places to store the surplus.

One of the key thefts you focus on in the book is the snatching of a copy of Poe's Al Araaf from the New York Public Library. What made this particular book such a desirable commodity at the time? And how did that theft turn out for the thieves in the end?

One of the key thefts you focus on in the book is the snatching of a copy of Poe's Al Araaf from the New York Public Library. What made this particular book such a desirable commodity at the time? And how did that theft turn out for the thieves in the end?

Al Aaraaf, Tamerlane and Minor Poems was Poe's second publication, but the first to use his name. Like much of his early work, because it had not been popular, few copies were saved. This, coupled with the fact that the value of Poe works had been party to an inexorable upward climb for three decades, made it a hot commodity.

I've tried to get my head around the "why" of the theft. The question "what were they thinking" is often hard to understand in retrospect, and I confess I can't be sure what the answer is. The theft from the New York Public Library seems to me a great deal like awaking a slumbering giant. The NYPL employed a man whose sole job was to keep its books safe—a unique position at the time—and had powerful allies in the city. When there were so many other compliant victims out there, why would anyone want to give the NYPL a reason to get involved? Recklessness? Spite? Because it was there? I don't know, but it spelled doom for the theft ring.

Tell us about the research for this book. What sorts of sources did you find that allowed you to reconstruct this theft ring and its deeds so thoroughly?

This book started out as a small part of a chapter in a larger book, when my only sources were a few newspaper articles and a New York appellate court case. Then I stumbled across a memoir that had a few pages on the theft and, very quickly after that, an article in a book collecting magazine from 1933. Each of these offered their own bits of information, each was written in an entirely different voice and each at different removes from the scene of the crime. Most of my previous research was based on court and law enforcement records—dry, fact-based, close-in-time material. The writing of this book, typified by those first sources, required me to draw on a range of much different sources to create a narrative.

Booksellers' memoirs—even if they did not mention this crime, or Book Row—were great, adding a certain life to the book. But there were also other types of first-person reporting that was extremely helpful: correspondence, court testimony, depositions, etc. These are more raw than memoir, because they aren't meant for public consumption, and so offer up little facts that a person would not ordinarily think to include in a more formal record.

I also read a lot of fiction from the time. Most of this was not helpful, except for providing context, but some bits and pieces made it into the story. There is even a little humor in the book, if you look hard enough. For example, I rely on a 1920s article from The New Yorker, at one point, to add levity to a passage; so you can probably guess that what humor exists is bone dry.

You've written and researched book thefts quite extensively in recent years. What are some of the most common misconceptions about this type of crime?

By far the largest, and most irksome, misconception is that there is some sort of mental illness associated with these crimes: that these guys are motivated by a compulsion to own books. There are definitely people who have mental issues that might compel them to steal and hoard books—Stephen Blumberg comes to mind—but most of these guys are in it simply for the money. Bibliokleptomania is, for most of these guys, a canard trotted out as a mitigating excuse for a credulous judiciary and public.

What are some of the ways book thefts (and their aftermaths) have remained the same since the time of the Book Row theft ring? Ways they're different today?

Book theft technique has remained remarkably stable over the years—which, I guess, is natural, given that there are only so many ways to steal a book. Squirreling away items in coat or trouser pockets, for instance, is the hardy perennial of library and archives theft. I think there is a perception that these thefts are different than they used to be. They aren't. The motivations, like the techniques, are the same as they ever were. One of the goals of my book, really, is to show several different historical eras and how the thieves, and their apologists, said basically the same things—sometimes, word for word—to excuse or explain their crimes.

The major significant difference is the internet. It has not done a whole lot to change the technique, but it definitely opened up the market—especially for map and archives theft—to amateurs. Twenty years ago, making money as an archives thief was hard; now, it is a lot easier. Of course, this is double-edged sword: selling items on eBay, for instance, opens one to the possibility that an honest person will recognize the thing as stolen, and make a phone call.

Tell us a bit about your own library: what sorts of books would we find on your shelves? How do you keep things organized?

I read a healthy mix of fiction and nonfiction, though, for leisure, I read the former more than the latter. I guess my general (though certainly not exclusive) pattern is to read recent nonfiction, and older fiction.

My organizational scheme is two-fold. Most of the books I have read are organized alphabetically by author. But my recent have-reads are organized chronologically, by when I finished them. That's because incorporating them into my shelves properly will require a major shelf shift, a task I've been leery of undertaking. There are about fifty books in this organizational limbo.

What have you read and enjoyed recently?

I don't read a whole lot of modern fiction, but a couple of living writers who I find absolutely captivating are Michael Chabon and Alan Furst. I've been reading Chabon for a long time, but I picked up Furst's Night Soldiers at the Joseph Fox Bookshop in Philadelphia while researching my book. Since then, I've been trying to keep myself from gorging his works in a big marathon read; I've managed to pace myself to one every six months. It gives me something to look forward to.

As for nonfiction, I'm reading Robert Hughes' The Fatal Shore, about the founding of Australia. We're going to Melbourne this summer, and I wanted to know something more about the country other than what you get from Outback Steakhouse commercials and shows about the world's ten deadliest animals. The book is terrific, and Hughes writes like a dream.

Have you embarked on your next project yet? Any hints as to what that might be?

I actually have two large nonfiction projects just about finished. One is something I think I'll probably release as an e-book (it is way too long for an article, and way too short for a book). It's the story of a long-term insider theft from an American college, and it's something I've been working on a lot as Thieves of Book Row has been in production. The other is a larger project I started six or seven years ago and it, too, is about a devastating series of library thefts—though more modern, and of a much different type than those of Book Row. This is what I anticipated would be my second book but, for a variety of reasons, got sidetracked. In a strange way, I think the book will be better for me having gone away from it for so long; I'm looking at it with fresh eyes.